After reading Unleashing Great Teaching (Clay and Weston, 2018) I was inspired to share my own professional learning focus. Admitting there is an area of your teaching that can be improved may lead to feelings of vulnerability and this is why it is particularly important that leaders model their own professional development. By doing this we are contributing to a professional environment where others feel it is safe to do the same.

So this is my professional learning focus:

What is the impact of ‘teaching concepts through examples’ on ‘describing specific musical features’ for ‘5th form GCSE musicians’?

The need

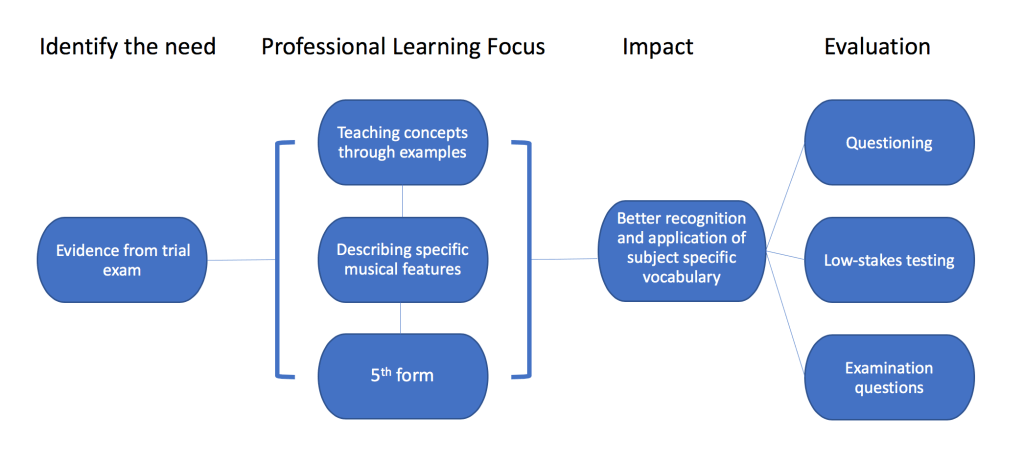

The 5th form trial exam brought to my attention some gaps in pupils’ knowledge. In order to cover all of the set works, as required by the Edexcel Pearson GCSE, I have been focusing on analysing set works and learning vocabulary as applicable to each set work. It is evident that pupils need greater understanding of the musical concepts themselves, outside the set-work frame of reference. There is unfamiliar listening in the exam; pupils need to have a general understanding of musical concepts to be successful in answering this type of question.

I have selected four concepts which the 5th form need to be able to recognise and describe in their GCSE music exam. These particular concepts were identified by examining student answers on the trial examination. Each of these concepts has a range of associated terminology and pupils need to be able to describe the concept using the correct terminology.

| Melody | Rhythm | Texture | Harmony |

The strategy

A ‘basic concept’ according to Engelmann is ‘one that cannot be fully described with other words’ (Engelmann and Carnine, 1982, p.4). To be taught properly it requires concrete examples. Basic concepts can be split into three different sub-groups and the one I am focusing on is ‘Nouns’ (multi-dimensional concepts, each one having many different features).

So why not just use words to describe or give a definition of the concept?

“The word is not the concept and does not imply the concept to a naive person.”

Engelmann and Carnine, 1982, p.16

My two-year-old son is probably the ultimate example of a naive person. He looks outside and can see the dew on the grass, or condensation on the car, and says “it’s raining, mummy”. You can see how he’s trying to marry the idea of water and rain together but he hasn’t quite got it yet.

We need to assume that our students are naive until we have thoroughly tested their understanding of a concept. I have certainly been guilty in the past of thinking a student ‘gets it’ until I see their test result. The breadth and limits of a concept need to be explored because students will have to recognise concepts in a wide range of musical genres and styles. Defining concepts is particularly relevant to music as students’ understanding is not complete unless they can ‘hear’ the concept; they must be able to identify it through listening. We have to make our meaning explicit and the best way to do this is through examples.

I have taken some questions from @Mr_Raichura ‘s blog post on this teaching method which will assist when planning these lessons:

- How can I introduce a concept through concrete examples, before using the abstract generalisation?

- Are there non-examples that I can use to help illustrate the boundary of the concept?

- What misconceptions could my sequence of examples/non-examples throw up?

- What questions can I ask to check for successful comprehension?

In addition Tom Needham’s chapter in the ResearchEd Guide to Explicit and Direct Instruction (2019) has informed my planning, in particular the ‘Juxtaposition Principles’.

- The wording principle – agree on standardising definitions for concepts as a department, write down what you intend to say for consistency, make sure definitions are not contradicted by later examples

- The set up principle – examples and non- examples should vary in only one way with all other features held constant – only one interpretation is possible.

- The difference principle – to understand what something is, it is helpful to comprehend what it is not. Examples and non examples should be juxtaposed consecutively (non examples highlight the concept boundary – non examples should share the surface features)

- The sameness principle – juxtapose maximally different examples to demonstrate the range and scope of a concept (examples should sample a wide domain. How to determine how many are sufficient? Test pupils)

“The closer that these principles are adhered to, the more likely the communication will be ‘faultless’ and the more likely a student will understand”

Needham, 2019, p.45

The impact

Firstly there is the impact on the learning of my pupils which I will evaluate through questioning, low-stakes testing and examination questions. I hope to see increased accuracy and frequency of use when applying this vocabulary to the set works and unfamiliar listening. A useful comparison can be made with the trial examination.

The second impact to consider is on the practice of the wider department and I hope to engage my whole department in this intervention as collaborative lesson research. We want to make sure pupils get the best results possible on their GCSE music exam; however, it is important that pupils understand these concepts as part of a good music education and important that we, as teachers, understand how pupils learn these concepts. The learning from this intervention is something that we can all utilise in our teaching throughout the year groups and we need to consider how we imbed this knowledge at an earlier stage in the course. Knowledge from this process will allow me to bring first-hand evidence to our departmental collaborative planning meetings about the effectiveness of explicit instruction. In this way the sharing of knowledge created from professional learning has a substantial impact on wider practice.

The third impact I am interested in is on pupils’ creativity. It is likely that enhanced conceptual understanding will feed into pupils’ composition work with greater knowledge and understanding paving the way for greater creative potential. This is harder to measure but would be fascinating to explore. The process of modelling these concepts for use in composition work (‘I do – We do – You do’) is another area that could be further developed.

The potential impact is huge and I’m looking forward to getting started!

References

Carnine, D. and Engelmann, S. (2016) Theory of Instruction: Principles and Applications

Clay, B. and Weston, D. (2018) Unleashing Great Teaching. Routledge

Needham, T. Teaching Through Examples, The ResearchEd Guide to Explicit and Direct Instruction (2019). Ed. Boxer, A. John Catt

https://bunsenblue.wordpress.com/2019/10/20/clear-teacher-explanations-i-examples-non-examples/