I think the principles of cognitive science can help us understand and explain many of the difficulties we may encounter in the music classroom. This is my experience of integrating some of the ideas from cognitive science into my own practice and using it to help understand the process of teaching and learning.

CLT

“Novice learners have limited abilities to process new information.” (Boxer, 2019). Although it makes sense when you’ve been teaching for a while (you learn to adapt your explanations and break processes down into bite-size chunks), an understanding of CLT helps explain why some things are so tricky, especially in the music classroom. Cognitive overload may also be the reason why some students insist that they are not ‘musical’. Music can be incredibly joyful, but it is not always easy to understand, compose or play music.

Reading music, playing music, staying in time with an accompanist/ensemble, and playing musically all at the same time is extremely demanding, and one of the reasons why music is so good for the brain. It helps to have an awareness of just how complicated this is and why pitching things at the right level in the classroom or for an ensemble, where there are so many different ability levels, is just so difficult.

It’s also been really interesting to think about CLT when explaining some of the trickier concepts, such as intervals, on the grade 5 ABRSM music theory paper. There are a lot of steps that need to be learnt, and if a pupil is still having to process letter names on the stave, then you can see why this is just so tricky for them.

Spaced Practice

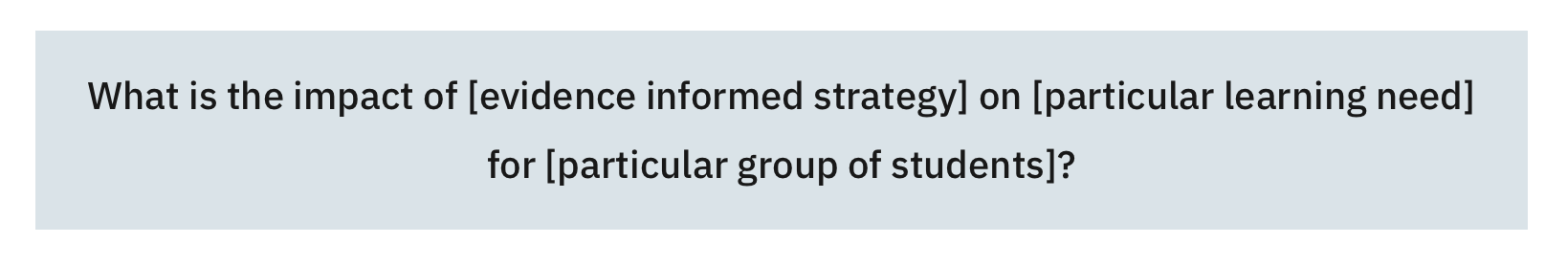

One of my key objectives for Year 9 music is to give pupils an understanding of the language of music so that they are able to engage in conversation about it, whether they decide to continue with the subject at GCSE level or not. For this reason returning to musical concepts and vocabulary to help pupils retain this knowledge happens frequently.

We’ve designed our GCSE, A-level and IB schemes of work with spaced practice in mind. Making sure we return to key concepts and vocabulary at regular intervals ensures students retain this knowledge. For example, at GCSE level we start the year looking at ‘melody’ and ‘what makes a good melody’. We incorporate this melody terminology into listening and retrieval exercises throughout the rest of the year. As we learn new concepts, we continue in the same way. We return to these through the process of composing; the concepts are made explicit through our teaching and pupils are able to demonstrate conceptual understanding by integrating these concepts into their own compositions.

Retrieval Practice

- Play/Sing/Clap the musical feature

- Blank score annotation

- Vocab grids

- Brain dumps

- Brain Book Buddy

- Mini whiteboards

- Focus on Sound quizzes

- Multiple choice quizzes

- Listening tests

- Listening at the start of Year 9 lessons to practice retrieving musical vocabulary, enhancing appraisal skills

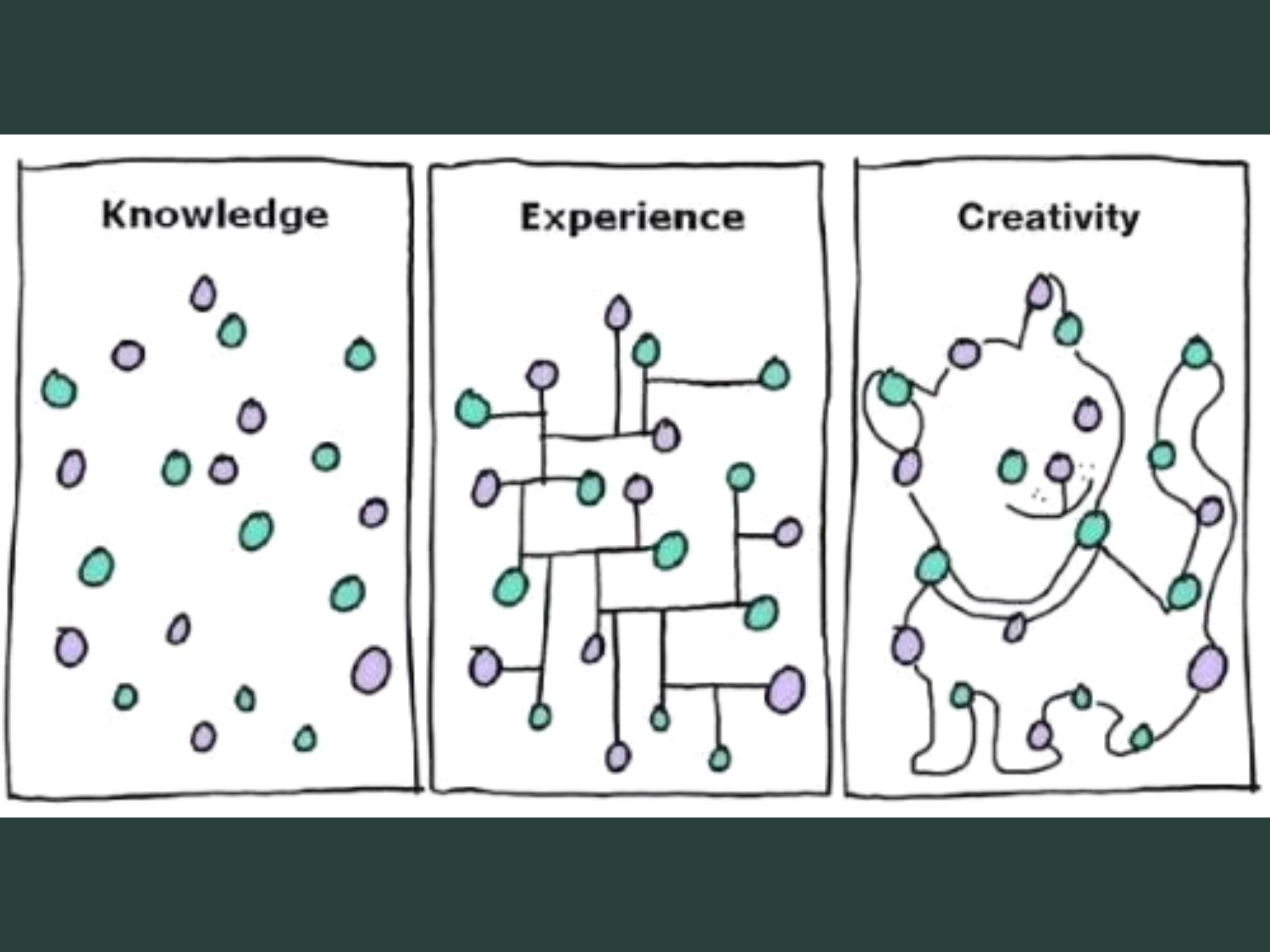

Elaboration

- Making connections between listening, performing and composing.

- Making connections between different set works.

- Making connections with a piece of music heard at a concert.

- Making connections with a student’s favourite song.

- A short composing task based on a specific musical concept

- Using subject specific vocabulary in sentences to check understanding.

- Using subject specific vocabulary in extended writing.

Concrete examples

- Singing/playing musical ideas to illustrate concepts/terminology

- Listening to examples in set works and other musical examples

- Creating own relevant examples by incorporating a specific concepts into composition work

Dual coding

We use this all the time in music, not just through words/pictures/diagrams, but through musical scores and listening:

- Annotating scores

- Listening and following a score (although this may be too complex to carry out simultaneously for those who cannot read music fluently)

- Using signs/symbols for specific concepts/terminology

Modelling/Scaffolding (I do – We do – You do)

We use this a lot when learning the process of composition.

Returning to the example of composing a good melody:

- The teacher models the composition of a melody to the class. Uses clear explanations of the process as he/she is working.

- The pupils contribute to the group composition of a melody. Misconceptions are addressed.

- The pupils compose their own melodies.

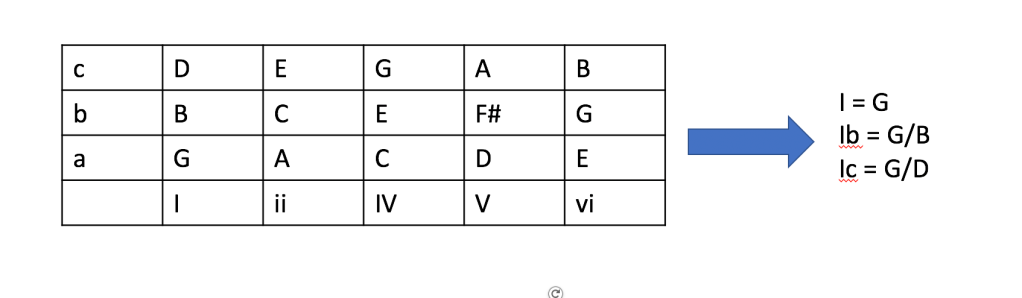

Learning how to harmonise a melody using I, II, IV and V

- The teacher models and explains how he/she is adding chords to the melody.

- The pupils suggest chords to add the melody. Misconceptions are addressed.

- The pupils harmonise their own melodies.

Motivation

We must pass on a love of music to our students so that they willingly engage with the vast array of musical culture that exists and is so accessible in the world today. We must also be aware of the evidence linking competence to motivation. I think it is vital that we learn the lessons that cognitive science can teach us to become highly effective teachers; this will help equip our pupils with a feelings of competence. We want them to identify as musicians. The hope then is that they will be motivated to study music past the age where it is no longer compulsory.

So there it is. Nothing ground-breaking here, but I’ve certainly found learning about cognitive science useful for informing some of the strategies in my own practice.

As music teachers I think we should be interested in the science of how we learn. This may or may not change our practice, but we should at least be aware.

For more, I recommend Adam Boxer’s excellent article

https://edu.rsc.org/feature/5-invaluable-lessons-from-cognitive-science/4010434.article

More on Brain, Book Buddy @effortfuleduktr